By 1836 with the onset of emancipation sugar estates in the less populated colonies of labour especially British Guiana and Trinidad began to starve economically. The need for labour caused planters to seek a new source and once again the idea of the Chinese labour came about. In Britain J Crawford forgot the 1806 flight from Trinidad and in 1843 he recommended that the Chinese be invited to settle in the West Indies under a system of indentureship since they thrived on the Filipino and Javanese sugar plantations. The Secretary of State agreed to let private contractors ship Chinese to the West Indies – 300 for Trinidad. But the shippers weren’t tempted by paltry sums offered and the plan foundered.

Chinese migration to British Guiana and Trinidad was more akin to that from India. Recruitment was supervised by an official emigration agent and all transport ships were licensed under the Chinese Passenger’s Act. Throughout Canton, emigration agent J. Gardiner Austin posted noticed emphasizing that there were no slaves on the British colonies; rich, poor all religions were subject to the same laws; conditions during the passage were regulated by British law; the West Indian climate was similar to that of South China; the West Indian colonies has special magistrate to protect immigrant labourers; daily wages were from two to four shillings; house ; garden and medical attendance were provided free; indentureship contracts could be cancelled once the remaining proportion of the passage money was repaid; contacts with and remittance to relatives at home were facilitated; advances of $20 was paid for a wife or each adult daughter bought along and $5 for each child; education of children was provided and women had no contractual obligation to work. They received no return passage as did the Indian indentures, but in all other respects the Chinese came on better terms however recruiters lied about how much an immigrant could hope to earn and the advance the immigrants were given landed them heavily in debt with the Trinidad Immigration Reports often claiming that suicide was prevalent among the Chinese with high debt. Migrants were usually refugees from the Opium Wars, the Taiping Rebellion and the Hakka-Punti clan wars. Immigrants comprised five ethnic groups: Hainanese, Fukinese or Hokkien (from Amoy), Teochin (from Swatow) and mainly going to the Americas, Cantonese and Hakkas.

The second group of Chinese immigrants to Trinidad arrived on March 4th 1843 via the Australia. Of the 432 Chinese men who disembarked; eight were hospitalized, three were dead and the rest sent to 18 estates in St. George’s Caroni, Victoria and St. Patrick. Later that month the Clarendon landed 251 more Chinese immigrants; two for hospital and the rest for 12 estates. Then in June the Lady Flora Hastings brought the plantations another 305 labourers from China. With them disembarked two Chinese doctors who had supplied the shipboard immigrants with opium until the stash was confiscated by the captain. All but 12 who were in hospital were assigned to 17 estates and almost immediately the planters began complaining. “The Chinese showed their temper before three week had passes, refusing to work, and insisting on full rations in the terms of agreements, which stipulated that no man should be mulcted in either allowance or pay, unless he were more than 14 days sick continuously” fumed Immigration Agent-General Henry Mitchell. “They in many instances laid up during 14 days and turned out on the 15th, turning in again on the 16th for the remainder of the month, and then claiming all the privileges of those who had done a full month’s work.

Mortality of that of the 988 Chinese immigrants at the time was high. After the arduous 3-5 month journey from China, many especially those further weakened by opium, succumbed to dysentery and infections. Within a year 86 of those from the Australia were dead, 31 on three diseased ravage estates. There was one suicide. Those who had been sent to Jordan Hill Estate quickly developed a taste for rum. At Orange Grove there was almost a Chinese riot.

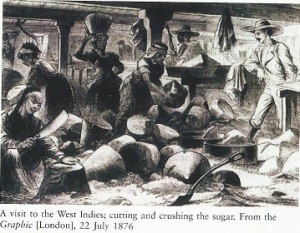

Yet those who survived adjusted, although initially, the planters were not pleased that the Chinese claimed their legal rights. They demanded full rations and full pay and if unwell they claimed their legal rights. They demanded full rations and full pay and if unwell they claimed the sick leave to which they were entitled. Conflict between the Chinese and the plantation owners and overseers was heightened by mutual incomprehension. Eventually as weeks grew into months an acceptable relationship was worked out with the presence of an interpreter. By the year’s end nine Chinese were in gaol for vagabondage and theft but most of the Chinese had taken to profitable market gardening and pig chicken rearing in addition to their estate duties. One of the Chinese doctors has returned home but the other married a local woman. In 1858 by the time the first indentureship period was complete, five years after the Australia and Clarendon had landed, there were only 665 Chinese recorded on census. Of these 225 had purchased themselves out of indentureship. Of the 310 still on the estates many now held supervisory posts on estates. Of those who had left many were independent. Many of the immigrants were shopkeepers, some quite wealthy.

The 467 immigrants who disembarked the Wanata on June 3rd 1862 were the first Chinese to arrive on the nine years since those aboard the Australia and, Clarendon and Flora Hastings. The Wanata group who survived the voyage and their new sickly environment quickly began to abscond. Two eventually repaid their advance, whereas 4 committed suicide to avoid it. Within two years only 179 men and three women were left on estates. Most of the other 122 women the first to come to Trinidad brought as wives for the $20 bounty had been repudiated by their husbands as destitute or worst than useless however there were exceptions. In 1865, the Montrose and Paria brought a further 593 immigrants (416 men) from Canton for 28 employers. Some of the women from the Paria even asked to work, the only such instance and overall planters were pleased with these immigrants. This was not so of the 597 who arrived from the Dudbrook and Red Riding which arrived in February 1866; forty percent soon deserted their plantations. Those who remained became burdens to several planters and were asked to be removed once they paid their indentureship fees. After that no more indentured Chinese immigrants came to Trinidad. Yet those who arrived between 1853 and 1866 did well once they settled in. Even while on the plantations they began rearing chickens and pigs and growing crops to supplement their meager incomes. On their own they climbed rapidly up the social ladder. They introduced certain vegetables, carrots, turnips, cabbages and were described by Louis de Verteuil as ‘the best gardeners in the colony.’ Some became pork butchers and some in San Fernando did a brisk trade in oysters while a few did well as cocoa dealers. The numbers of Chinese in jails fell as they all entered the retail trade and opened merchandise shops. Men such as Louis Atteck, who came aboard the Wanata in 1863 and was redeemed from the indentureship shortly after by one those Chinese shopkeepers, by 1877 had his own shop in Princess Town, a large cocoa estate in Tableland and was mentioned in the Trinidad Chronicle as being worth about twelve thousand pounds of fortune.

Sources: [Johnson, Kim “Descendants of the Dragon” Ian Randle Publishing, 2006.]

Previous Page: First Wave Next Page:Third Wave of Chinese Migration